Joy & Pain – Chapter #5

As 1978 morphed into 1979, something odd happened – skateboarding suffered its second bust. It felt like the rug had been pulled under my feet. My constant practice paid off, and the fusion of punk rock and skateboarding kept me super motivated. But I kept wondering, “Hey, where did everybody go?” Skate shops and skate parks closed. It was such a jarring and bewildering experience. I became the only kid in my neighbourhood still skating. I couldn’t really understand what happened. All I knew was that one day, it was skateboards, and then it pivoted to BMX, and I wasn’t interested in bikes.

There is an expression that I’ve heard numerous times that I feel fits this chapter beautifully: “The one thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.” Over the following chapters, I will explain each of the crashes I’ve witnessed in skateboarding. Regardless of age, you can learn much from the boom/bust cycle that plagues the industry and participants with alarming regularity.

To understand the whole picture, we must examine what happened during skateboarding’s first big bust, two years after I was born – 1966. The bust was due to poor technology (clay wheels!) and media coverage focusing on skateboard injuries. Doctors were very upset by the number of injuries and publicized their findings. The media picked up this, and cities started banning skateboards. As a result of these concerns, retailers wondered about liabilities and insurance, so they removed skateboards from their shelves.

75,000 skateboard orders cancelled in one day.

I had an opportunity to interview Larry Stevenson, the founder of Makaha Skateboards and one of skateboarding’s pioneers. He actually patented the kicktail. At the height of Makaha, they sold 4 million dollars worth of skateboards in one year. This is equivalent to over 40 million in 2025. But then, it all started to collapse. It was truly painful to hear his story of getting 75,000 skateboard orders cancelled in one day.

It might be worthwhile to quote Frederick Nietzsche – “Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” But the sad truth is that when something you love completely implodes, it can be devastating. Time gives you the opportunity to ruminate about what could have been or what decisions could have been made differently.

Interestingly enough, a few people, mainly in Southern California, kept skateboarding despite this bust. Most of them were surfers. The surf craze of the late 50s was the catalyst for “sidewalk surfing” in the 60’s. However, when skateboarding died in 1966, it set the groundwork for people to work on technical innovation without commercial pressure. Frank Nasworthy was smart to move to California and cultivate demand in the only place where people craved something like an advanced wheel.

From fad to true subculture

The way I view it is that there were millions of people riding skateboards in the 1960s, but there were very few skateboarders. This has repeated itself with every boom and bust. You could say only the truly committed stayed with skateboarding after 1966. When skateboarding moved from a fad to a true subculture, it grew in strength but not size.

When skateboarding took off in the mid-70s, some astonishing things happened. At one point, it was estimated there were over 20 million skateboarders in the USA alone. Unfortunately, due to this increased participation, visits to hospital rooms shot up. This moved public perception from viewing skateboarding as a wholesome recreation to a dangerous activity. This led cities ban skateboarding again!

Adding to this was the oversaturation of the product. So many people wanted to cash in on the skateboard craze (again) that it led to a glut of crappy, low-cost products. When demand shrank, the skateboard industry collapsed.

Over 200 skateboard parks were built in North America. Sadly, 80% were closed due to insurance costs. However, adding to this was that some owners could make a bigger profit by turning the land into either houses or shopping malls.

Throw in the late 70s economic downturn that reduced discretionary spending and it was a recipe for disaster. The energy crisis made petroleum-based products like plastic more expensive. BMX also exploded onto the scene the same way skateboards had done and started to capture a younger generation’s imagination.

It was a case of Deja vu all over again. Casual participants abandoned skateboarding while hardcore enthusiasts remained. This audience was smaller but deeply committed. As skateboarding got more infused with punk and alternative cultures, it alienated the family-friendly demographic that had fueled the boom. As things got more rebellious, it turned many prospective customers off and upset skaters who weren’t down with all the negative attitudes.

As for me? I didn’t have the luxury of living near one of the skateparks featured in the skate mags. In fact, the magazines moved away from slalom, downhill, freestyle and other genres to focus primarily on vert. This myopic view didn’t help the situation. My local skatepark consisted of a few wooden ramps inside a hockey rink. It closed in 1979 and never reopened. The local bike shop with an extensive selection of skateboard products returned strictly to bike gear. I must admit that while I still skated, it took a back seat to music and girls. I got a set of drums and started playing in punk bands. I also became obsessed with becoming a disc jockey.

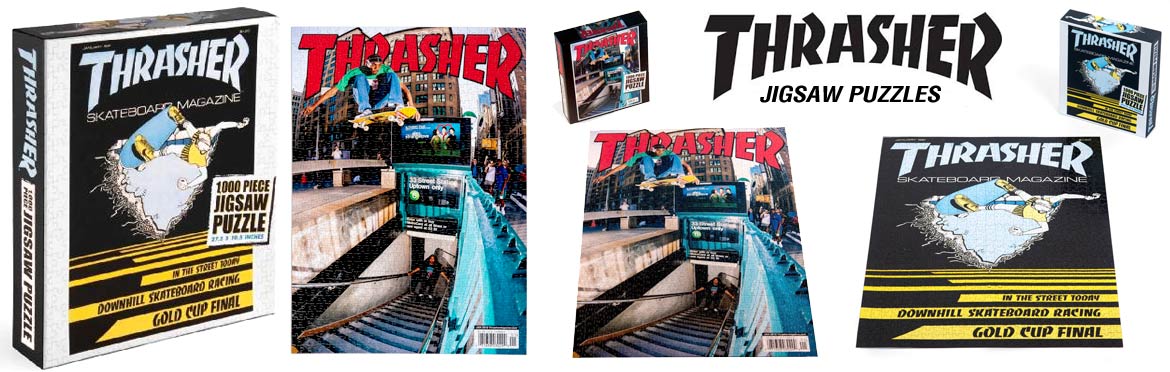

But just like in the 60s, a small contingent of skaters remained committed to skateboarding. The focus was on do-it-yourself and backyard ramps sprung up across the globe. While SkateBoarder morphed into Action Now, a group of skaters led by Fausto Vitello and Eric Swenson (of Independent Trucks) decided to go in a different direction. Thrasher Magazine debuted in January of 1981 to connect skaters worldwide. I distinctly recall seeing a copy in 1982 in a record shop I’d frequently visit. In truth, I was intrigued but didn’t plunk down the money to buy it like I had done with SkateBoarder Magazine six years earlier.

Pockets of people

Looking back, I understand why my passion for skateboarding may have waned somewhat. It’s easy to see how priorities change when you’re a teenager. Skateboarding in the early 80s was something I did infrequently. But each time I skated, I enjoyed it. At the same time, I knew that I’d never feel comfortable leaving skateboarding completely. This is why I left my hometown in the late summer of 1983 to attend school in Toronto; I brought my skateboards.

It should be evident to anyone reading this that there are always pockets of people who continue to do their part to cultivate a tight-knit community, no matter how much skateboarding shrinks in popularity.

If you want proof of how impactful small numbers can be, look at Zoroastrianism. Chances are you’ve never heard of this religion, which debuted over 3,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest religions in the world. The core tenets of Zoroastrianism significantly influenced Judaism, Islam, Christianity and Buddhism. But here’s the most mind-blowing part: the estimated number of practicing Zoroastrians today is approximately 125,000 in total.

To put things in perspective, there are approximately 85 million skateboarders worldwide. Even if 10% of the population are considered core skaters (who ride numerous times a year), that’s still over 8 million people.

At the core of being a life-long skateboarder is to recognize that while your body might not be able to do everything it did in the past, your mind is still free to develop and be challenged. If skateboarding is an activity you can do alone or with a group, it makes no difference whether it’s popular or not.

SKATEBOARDER Magazine first dropped four rare issues in 1964–65 before disappearing into the void—until its epic resurrection in 1975. By 1981, it had morphed into ACTION NOW Magazine, shifting gears to spotlight the exploding world of alternative sports: BMX, sandboarding, snowboarding, and more.

What you’re looking at here is the lost pilot episode of the never-aired ACTION NOW MAGAZINE TV show. Featured: legendary Jack Smith, pioneering sand/snowboarder, rolling in with his custom A-TEAM boards. Plus, rare footage from the iconic Pipeline Skatepark.

This show never made it to air—but if it had, it would’ve been decades ahead of the curve.